This post explains my use of Instagram to share digitised photographs from the Powell-Cotton Museum collections, with the aim of increasing access and raising awareness of the collection among Somali and Somali diaspora audiences. I am not a professional social media manager, so I made use of available tutorials and advice, and applied my ideas about collections engagement to creating Instagram content.

Part of the inspiration for this project was the ability for photographs to circulate online outside of the museum’s sphere of control. Once some of the photographs from Diana Powell-Cotton’s trip to southern Somalia had been digitised and shared as part of the British Museum’s Object Journeys project, they had begun to appear elsewhere online, shared on social media and on WhatsApp. Rather than attempt to control the circulation of their collections, the Powell-Cotton Museum wanted to embrace the fact that people were interested in these images. In discussion with museum staff, we thought about ways that we could get the images out there, while making it easy for people who were interested in finding out more to contact the museum. To do this I created linked Instagram and WhatsApp accounts. You will be able to read about the experience of using WhatsApp for collections engagement in an upcoming companion post.

Instagram basics

Although my aim was simply to increase awareness of the collection, not to drive sales or any other specific business goal, I knew my use of instagram wouldn’t be that different from most business accounts. So I followed some basic advice for increasing engagement:

I posted consistently

Once I had got the account up and running and done a few test posts, I committed to posting every weekday (and some weekends) during the course of the project. I shared 74 grid posts, with a mixture of single and multiple images per post. Each post was a black and white photograph; I occasionally included images of museum objects or field notes where relevant, but never as the first image in the carousel, so the grid is also visually consistent.

I followed some similar accounts and liked and commented on their posts

There are several popular accounts that share found photographs and archive footage from Somalia. I generally only followed and commented on accounts that posted in English because I don’t speak Somali and didn’t want the museum to be seen to be endorsing anything if I could not understand the content. This is an obvious shortcoming of being a non-Somali museum professional working on these collections. While browsing these accounts I found a couple of instances of Powell-Cotton photos from the Object Journeys site being shared. I commented, thanked the account for sharing and directed them to the new account where they could see more photos. These comments were well received and helped me to get more followers on the account.

I looked at the hashtags that people were using to share similar images.

I tried a few different styles of hashtag. I used tags that similar accounts were using for historic photographs such as #VintageSomalia. I tagged specific place names where I knew them, using the contemporary Somali names for places, as well as broader terms like #Somalia and #HornofAfrica. For posts that showed a specific craft, musical instrument or game, I used hashtags related to that content to attract a different audience to the post.

I posted timely content

Some of the most joyful pictures in Diana’s collection are those she took during Eid. In her album captions she describes the occasion as ‘after the fast of Ramadan’, but when I looked at all her diaries, and the dates and locations of her travel, I realised this was a mistake. The festival which fell in her first weeks in Somalia in March 1934 was Eid al-Adha, not Eid al-Fitr which follows Ramadan. Eid al-Adha 2022 fell in July as I was working on the project, so I was able to share these images in a series of Eid themed posts, which were some of my most popular.

How much information to include in photograph captions for Instagram

While the trend on Instagram is towards longer captions, I didn’t always have a lot to say about the images I was sharing. I wanted to keep things simple and start getting some content out there. One of the things I wanted to investigate with this project was how much documentation work do we actually need to do before we start sharing collections?

I have always argued that museums at least need to have an idea of what they have and where, and where it came from before they open things up to audiences. This is partly because I think it is the museums responsibility to maintain this information, but also because there is more chance of engaging an audience with collections if there is some context to what they are looking at. In my initials meetings with potential audiences, people were interested to know more about Diana Powell-Cotton and how she had come to take these photos. I used the story highlights feature to pin a story with some key information about Diana and the museum so that I did not have to keep repeating information in each post.

Some other practitioners, such as Jocelyne Dudding who spoke at the Museum Ethnographers Group Keeping Connected event which I co-organised, have found that some audiences care very little about what museums have to say in their records and captions. Jocelyne described how MAA have created a specific view in their collections database to meet the needs of researchers who are more interested in the photograph itself than the museum’s commentary on it.

In this case I was trying to share images at the same time as I researched them, rather than waiting until the end of the project when I could hope to write a more comprehensive caption. One of the benefits of Instagram is that, unlike Twitter, you can go back and edit a post. I was able to do this once I had gathered more information about an image from project collaborators and from my archival research. I wanted to show that the information about the collections was evolving, and that the museum was open to new input from audiences.

Instagram’s move towards video

While I was working on this account, the big topic in the instagram community was the pivot to video. This was not a good time to be using Instagram as a photo sharing app. Because the Instagram algorithm now favours video content, I was concerned that despite my efforts, my static photo posts would not get as much engagement as if I was able to post video. I did make use of Instagram Stories to share more information about the photographs in time-sensitive posts, but I did not have the scope to create video content related to the images, and did not want to dilute the account which was supposed to be showcasing these photos.

Encouraging engagement

A typical way to encourage engagement and comments on posts is to ask questions in the captions (think of an influencer asking their followers ‘What are you grateful for today?’). I found it quite hard to get natural sounding questions into my photograph captions. The main question I wanted to ask ‘Do you recognise this person?’ was much too specific and unlikely to get a positive response, and asking broad and vague questions around the places and activities depicted in the images felt superficial. This is especially true as I don’t have enough knowledge about Somali culture to ask meaningful questions. Instead, I stuck to writing about the photographs and about the process of digitising and researching them, something I did feel qualified to write about.

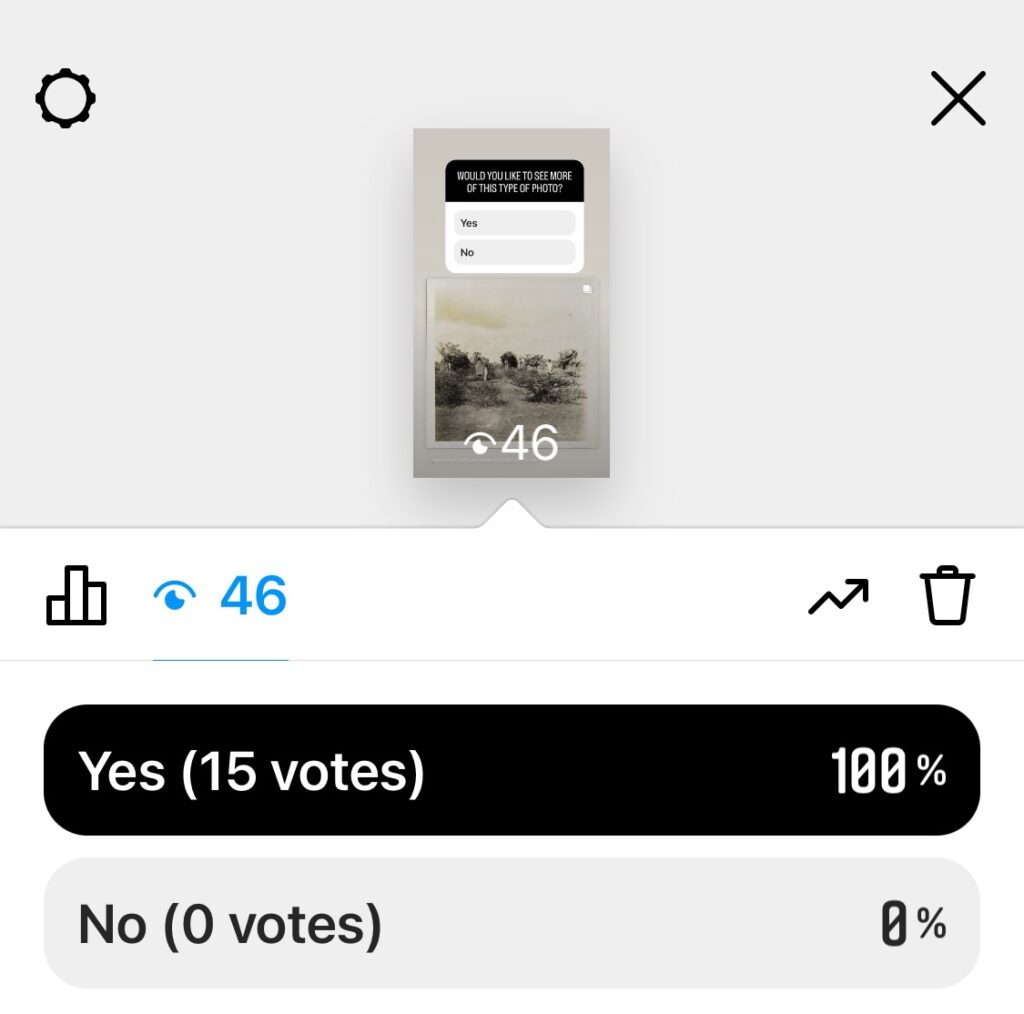

Again I made use of Stories to share more informal and timely information about the project. Rather than writing questions in the caption for each post, I used Stories to run polls about the kind of content I was sharing. For example, when I happened to share a post that unexpectedly got a lot of likes, I did a poll to ask followers if I should share more similar posts. I also polled followers about what topics they found more interesting.

Again I made use of Stories to share more informal and timely information about the project. Rather than writing questions in the caption for each post, I used Stories to run polls about the kind of content I was sharing. For example, when I happened to share a post that unexpectedly got a lot of likes, I did a poll to ask followers if I should share more similar posts. I also polled followers about what topics they found more interesting.

Analytics

Using a professional Instagram account gives you access to more analytics tools than a personal account. This allows you to see trends in engagement with your posts. While most museums use social media for marketing and engaging people with their wider programming, using Instagram strictly for showcasing collections makes it a great tool for understanding which areas of the collection people are most interested in, as well as what kind of captions and keywords (in this case hashtags) people respond to the most. Used in this way social media is a really powerful tool for understanding how people respond to collections.

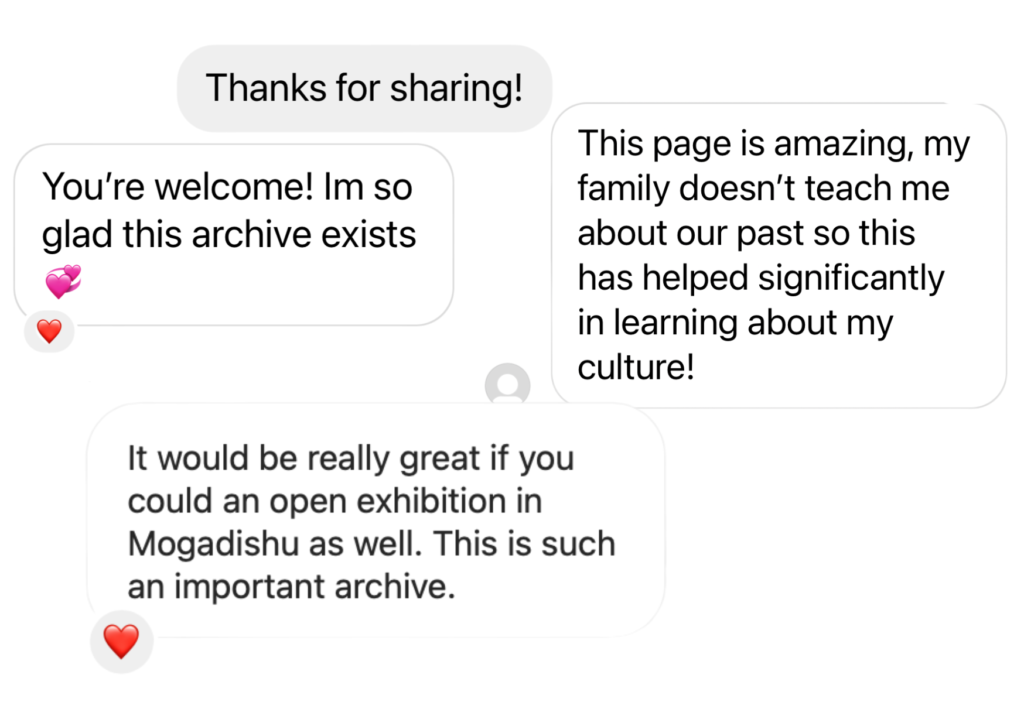

Quality not quantity of engagement

By the end of the project period, the Instagram account has realised almost 200 followers. This may not seem like a lot but I was very happy with the engagement on the account. Although Instagram analytics do not show breakdown of locations of followers, it is clear from the profiles (pictures, names, bios, Somali flag emojis and locations) that the vast majority of these accounts are young Somali and Somali diaspora people. This was a key target audience for these collections. While I did not get very many comments on my public posts, I received several direct messages from people who were very appreciative of the content I was sharing.